My origins as a postal historian have roots in my early interest in

collecting postage stamps (philately). As a kid on a shoestring budget,

my first source of stamps for collecting came from mail items that my

family received, closely followed by stamps torn from covers that were

saved by relatives. The postal historian in me shudders that I may well

have been responsible for the destruction of some interesting covers.

But, if it were not for the willingness of people to at least salvage

the stamps on my behalf, I may never have explored postal history at

all.

With my limited income, I could still go down to either the

music store, which had some stamps and supplies for collectors, or the "five and dime,"

and periodically pick up a packet of mixed stamps. On those days I

could be found spending way too much time trying to pick the packet that

had the most "new to me" stamps visible in the envelope through its

clear window. I even "splurged" one day for a BAG of stamps.

That

bag introduced me to the thought that not all stamps have the same

value to a collector. Especially when your bag of 1000 stamps had about

fifty exciting and new stamps and then multiple copies of other, less

exciting, stamps. For example, there had to be at least one hundred of

the three-cent purple Jefferson stamps of the 1938 Presidential Series, which was produced through 1954. Let's just say there was a significant amount of "buyer's remorse" after that purchase.

The

three-cent purple stamp paid the most common postal rate for a simple

letter mailed within the United States. Which means, of course, there

were (and still are) lots and lots of covers featuring this stamp - like

the one shown below:

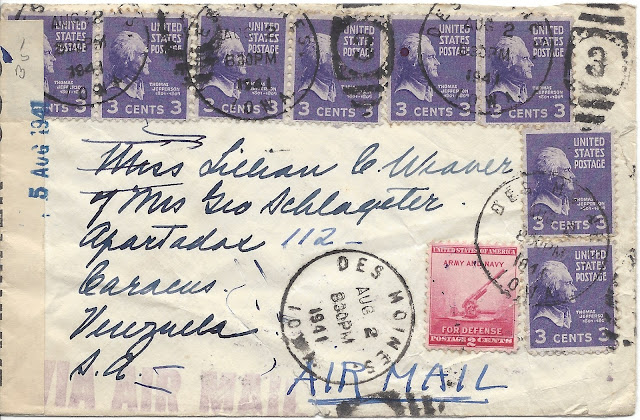

This

cover is actually a pretty nice looking example of a typical simple

internal letter paying the 3-cent rate for the United States. The cover

is in good repair. The markings are all clear. The address and return

address are easy to read. The postage stamp has a nice color, is well

centered, and in good repair. Even the envelope is a nice shade of blue

rather than a dingy white.

But, it still has that darned purple fire starter!

My

partner, Tammy, joked many years ago that we should take the hundreds

and hundreds of copies of this stamp I had in shoe boxes, bundle them up

and use them to start fires. Or, maybe we could dip them in wax and

make candles out of them. And, I'll tell you that the disappointed

young collector wasn't entirely upset by this suggestion. But, the

collector in me always balks - because you never know when you might

find something special.

Other Fire Starters

Postal

history is not immune to the concept of "fire starters." The most

common piece of saved mail will be a simple letter that shows a typical

use of the most common stamp and/or most common markings for that period

and place. If there was a reasonable amount of mail volume in the

first place, there will most certainly be a class of items that will be

plentiful enough to make the collector say, "Oh... another one of..

THOSE."

For example, the 1861 US series of stamps I favor also

features a three-cent stamp that paid the rate for a simple domestic

letter. There are lots of examples of this stamp on cover that survive

today - even after 160 years. If you wanted to add a piece of real

history in the form of an old envelope, you could do so for very little

cost. In fact, if you're not picky about how it looks, there are people

who might happily gift one to you if you showed real interest.

So, why would someone want to pay attention to them in the first place? What makes one of these fire starters worth attention?

For

the 1861 cover shown above, you might notice that it is also a clean

and well preserved cover, despite its age. That, in itself, is a good

start. The color shade of the stamp provides some interest, as do the

blue postmarks. It's a neat curiosity that the year date is upside

down. And maybe the addressee is of interest. In short, there are many

ways a piece of postal history can get our attention - even if it is

associated with something that can be found in abundance.

Exceptions to the rule

Just

because a three-cent purple Jefferson is associated with the most

common type of US domestic mail in the 1940s, it could still be used in

combination with other stamps. For example, here is a 1947 envelope

that includes a Special Delivery stamp that was intended to pay for

additional services.

Once again, the cover is in good shape and it

looks pretty nice. But, there is also the possibility that there is

more story to be told with this item.

Then

there is this letter that was mailed from Des Moines, Iowa, in 1941 to

Venezuela. This letter took the more expensive Air Mail services to

speed its delivery. It was also inspected by a censor on August 5, with

World War II actively engaged - even if the US was not directly

involved at the time.

Once again, this letter clearly has more

going on than a simple domestic letter. Even if you are not a postal

historian, you would probably notice this envelope if it were in a pile

of covers that looked like the first one I showed for this article.

But, what if I show you this one?

Yes.

It's a simple, domestic letter. It has that darned fire starter stamp

on it. If it were in that same pile of covers, you might not notice it

if you quickly flipped through everything - because, for the most part,

there's nothing that easily makes it stand out.

But this envelope is part of a very important story that is part of United States World War II history.

Executive Order 9066

On

February 19, 1942, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed Executive

Order 9066. This order directed the War Department to establish

"military areas" where anyone could be excluded from access. This

action came about due to increasing public pressure based on growing

anti-Japanese hysteria. Top government officials, such as Attorney

General Biddle and Secretary of War Stimson did not necessarily feel the

move was a good one and worried that it might not be legal. But, those

who insisted the policy was needed to ensure public safety on the West

Coast convinced them to recommend the action to the President.

Executive

Order 9066 allowed the military the power to remove persons of Japanese

descent from California, Oregon and Washington. The War Relocation

Authority was created and a system of Assembly and Relocation Centers

were created. Most Assembly Centers were fairgrounds and racetracks on

the West Coast. Santa Anita Park, an equestrian racetrack in southern

California, temporarily housed detainee families in horse stalls.

There were ten Relocation Centers

that are more accurately described as prison camps. While each camp

included schools, post offices, work facilities and land to grow food,

they were also surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers. Those who

were labeled as dissidents were sent to a special prison camp in Tule

Lake, California. Two camps were located on Native American

reservations despite protests of the tribal councils there.

By August of 1942, approximately 112,000 persons

were sent to the Assembly Centers for processing to the Relocation

Centers. Two-thirds of these people were citizens of the United States

and had not been charged with disloyalty to the US. Still, they had no

mechanism to appeal their detention and loss of property. They were

forced to leave homes, jobs, businesses and communities, along with most

of their possessions, and when they returned at war's end, many found

what they had left behind was gone.

Heart Mountain

One of the prison camps was located in Wyoming at Heart Mountain.

This Relocation Center consisted of a 740 acre site that included 650

buildings (450 barracks) and was surrounded by barbed wire and nine

guard towers. At its peak, over ten thousand people were confined at

this camp and those incarcerated there grew their own food on 1,100

acres of nearby land.

Barracks were laid out in blocks separated

by unpaved roads. Kiyoshi Honda, our letter writer, lived in Block 17,

according to his return address. Each block consisted of 24 barracks,

two mess halls, two latrine buildings, laundry facilities and two

recreation buildings. The address "Block 17 - 3 - B" identified the

writer's barracks building.

There

are several resources that discuss the history and events surrounding

the imprisonment of Japanese peoples during World War II in the United

States, but the best resource I have found thus far is the Densho Encyclopedia.

I strongly advise interested readers to visit that site, which includes

recorded oral histories in addition to images and other materials.

Much of the details that follow for both Heart Mountain and Camp Amache

were gleaned from their materials.

The

location for the Heart Mountain site was not selected for

habitability. Instead, the location was intended to isolate the

internees from the rest of the population. The land was barren and

unwelcoming, especially considering where most detainees had lived prior

to their arrival at Heart Mountain.

The Heart Mountain site

started rapid and slipshod construction of the necessary buildings in

June of 1942. While around 2000 people were employed in the building

process, construction experience was deemed unnecessary - if you could

drive a nail with a hammer, you qualified. While construction of over

500 buildings were completed by August, most were poorly suited to

withstand the extreme weather typical for Wyoming. Doors and windows

were often poorly installed and would not close completely. Detainees

began arriving in mid-August and did what they could by hanging spare

sheets and stuffing cracks with rags and newspapers.

The Heart

Mountain prison camp is known for the acts of protest undertaken by

members of the detainee population. Rather than paraphrase, I thought

the following from the Densho Encyclopedia would serve well:

"The latent antagonism between Caucasian authorities and inmates came to

boil ... when military police arrested 32 young

children for sledding outside of camp boundaries. Although the children

were released to their parents, inmates were quick to condemn the

treatment of the children by the police. Amidst rising tension the army

attempted to recruit volunteer workers to construct a barbed wire fence

around the perimeter of the camp. The majority of working-age men went

on strike, refusing to participate in the project. They questioned the

army's justification for erecting the fence; namely the attempt to keep

stray cattle from entering the campgrounds. Three thousand inmates

signed a petition "charging that the fence proved that Heart Mountain

was indeed a 'concentration camp' and that the evacuees were 'prisoners

of war.'"

Of course, there was an effort by

government to use semantics to justify the forced removal of these

people from the West Coast while still making it sound less like they

were actual prisoners. Detainees at Heart Mountain were clearly aware

of the picture being painted in the press that worked to put a good face

on the matter and they were not willing to accept that without a

struggle.

Camp Amache

Camp Amache,

also known as the Granada Relocation Center, is located near the towns

of Granada and Lamar, Colorado. This Relocation Center provides an

interesting contrast to Heart Mountain. Colorado's Governor Ralph Carr

was the only western governor to support the establishment of a

Relocation Center in his state. The administrators of Camp Amache were,

in general, considered to "have a deep regard for fairness" and some of

the teachers petitioned to move to the camp so they could better serve

their students.

The agricultural efforts of the detainees were

fairly successful, producing over 4 million pounds of produce in 1943

alone. The camp even had a silk screen printing shop. Established in

June of 1943, the Amache silkscreen shop produced over 250,000 color

posters under a contract with the US Navy.

The sender of this letter, Sam Okubara,

actually served in the US Army after World War II in Japan as a

language instructor (presumably teaching the Japanese the English

language). The relatively "friendly" conditions at Camp Amache

correlated with higher numbers of volunteers for military service.

The following also comes from the Densho Encyclopedia:

"A total of

953 men and women from Amache volunteered or were drafted for military

service during WWII. Of this number, 105 were wounded and 31 killed in

action. Among those killed was Kiyoshi Muranaga who was awarded the

Congressional Medal of Honor

. However, not all Amacheans responded favorably to the notice for

induction into the military. Thirty-one men from Amache were tried for

draft evasion, found guilty, and sent to prison in

Tucson, Arizona."

I think it is important to point

out that, while Japanese people in these camps were denied their

freedoms, they were still subject to being drafted for military

service. I don't think it takes too much imagination to understand why

many of those drafted would be inclined to say "no" and accept the

punishment of doing so in protest.

The Okubara family was forcibly removed from their home in Mill Valley, California in April of 1942. The Spring 2019 Mill Valley Historical Society Review

features the story of the removal of Japanese citizens, including the

Okubaras. The Mill Valley Public Library includes images of the family,

including the one shown above. Sam can be seen as the second person

from the right (in uniform). Sam's parents, Tora and Harry can be seen

at the left.

While Tora would die from heart failure at the camp

in 1945, both Sam and his father would return to Mill Valley at the end

of World War II. Sam would then depart to serve in Japan soon after.

The story in the Mill Valley Historical Society Review is worth a read

if you want to get a better flavor of events for that community.

While

detainees found themselves in less than desirable situations, they

still did what they could to build community. Many of the camps created

their own newspapers as evidenced by the masthead of a May, 1944

edition of the Granada Pioneer (Camp Amache) shown above. Reading the

contents of these papers show the tensions that reflect the rejection of

their loyalty to the land in which they lived and their connections to

their homeland or the homeland of their ancestors. They also reflect

what was likely a wide range of opinions regarding how they should react

within the population of prisoners in these camps.

| From Oct 14, 1942 Granada Camp Bulletin

|

|

|

The Granada Pioneer had its start as a camp

bulletin that began publication on October 14, 1942. In that issue, it

becomes clear that the addition of several thousand people to a small,

rural population did not come without significant strain on the existing

communities. One article makes note (shown above at left) that the

rural Granada post office struggled to handle the sudden boom in mail

volume. Another mentions that passes to shop in Lamar were not going to

be offered because internees had cleaned off the merchants shelves,

leaving nothing for the local farmers. Subsequent bulletins for the

next week indicate that rapid adjustments were being made and the Lamar

Chamber of Commerce was now courting business from those at Camp Amache.

While

the War Relocation Authority named this the Grenada Relocation Center,

the US Post Offices recognition of the name Amache seems to have

resulted in the latter name receiving more use. By the time this letter

was sent, the post office in the camp had its own cancellation device,

though I expect it was in use sooner than this.

And finally, you

might notice that both envelopes were addressed to the newspaper named

the Denver Post. Sam Okubara's letter may well have contained payment

for a newspaper subscription since his letter was addressed to the

subscription office. However, a very faint marking on that envelope

indicates that it was in the Steno Department on the 17th of October.

Since

there are no contents, we can't be wholly certain of anything. Though

it seems odd that a mere subscription would require the efforts of the

Stenographer Department. If anyone has insight on this, I would be

happy to hear it.

And that is how two of what must be many fairly

common-looking covers elevate themselves well above firestarter status.

They shine a light, without being subjected to burning, on a time in

history that we should contemplate and learn from. Thank you for

joining me today. I hope you have a fine remainder of your day and an

excellent week to come.

Bonus Material - the Prexies

The

1938 Presidential Series is often referred to by philatelists as the

Prexie Series or the Prexies. And, of course, there are people who love

to collect and explore the history and postal history that surrounds

them. The United States Stamp Society has a nice overview of the entire issue that you can look at if you want to learn more. This online exhibit by Hal Klein can give you an overview of the rates these stamps could pay.

If you like even MORE detail about the stamps and their production, you can go to this page on the Stamp Smarter site.

It is here that you might notice the stamp production numbers for each

denomination. The three-cent Jefferson had a total production level of

130 BILLION copies during the 1938-54 period. The next highest

production number for a denomination in this issue is about a quarter of

that. Now you might get an idea of why there are so many of them out

there.

Yet, despite the relatively common occurrence of this

particular stamp, a person can find truly interesting, and very

worthwhile, things.

---------------------

Postal History

Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.