Welcome to this week's edition of Postal History Sunday.

I'd like to start by acknowledging the many kind words passed my way at Westpex by individuals who have enjoyed these writings for the past (almost) three years. I heard from persons who I would consider to be very knowledgeable postal historians and others whose expertise landed in philately (postage stamps) and revenue stamps. I even heard from one individual who was not terribly interested in any of these hobbies - though they were exposed to it by being related to an individual who is.

I am aware that there are many who read Postal History Sunday that might not know what a "Westpex" might be. Westpex is an event that could be likened to a convention where persons who are interested in postage stamps, postal history, revenue stamps and (sometimes) other paper collectibles gather. There are many such shows that occur in various locations. The letters "pex" for "philatelic exhibition" are typically added to create the name of the particular event - like Chicagopex, which I have mentioned in the past. Westpex was held in San Francisco last weekend.

The other thing I was reminded of is that there is still some mystery as to how my last name should be pronounced. For those who do not know, my name is Rob Faux - and the last is pronounced "Fox."

Mystery solved!

Philatelic exhibitions provide collectors, such as myself, opportunities to view and perhaps acquire new items for our collections. I thought I would share a couple of items that caught my attention and some of the reasons I found them interesting.

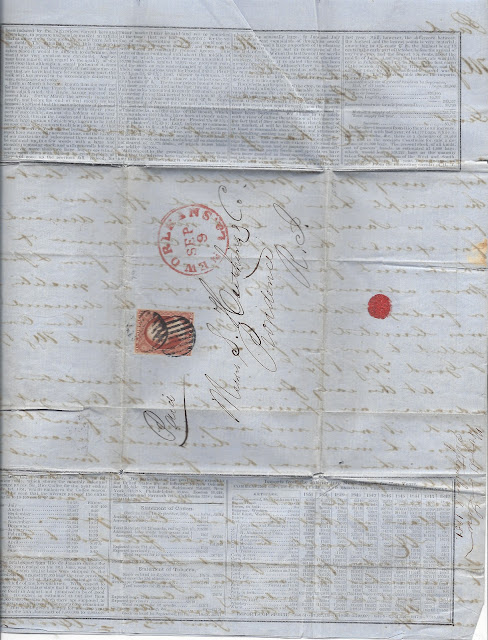

Shown above is a folded letter that was mailed at the New Orleans (Louisiana) post office on September 9. It is not hard to see why I came to that conclusion - based on the big, red, circular date stamp at the top left. The three cents in postage were paid by the stamp and that stamp was canceled with two round grid markings in black ink. We often refer to a used postage stamp as having received a cancellation, which refers to the various postal markings intended to deface the stamp and make it difficult for someone to reuse it.

An Act of Congress issued on March 3, 1851 reduced the letter rate for mail in the United States to 3 cents per 1/2 ounce for items sent no more than 3000 miles (effective on July 1 of that year). At the same time, a 3 cent postage stamp was issued to show prepayment of this rate. In addition, this act authorized the creation of a 3 cent coin (the first of its type) to provide the public with a convenient method to pay for these stamps.

If you are interested in a summary of the internal US postage rates at the time this folded letter was mailed, it is shown below:

Letter Mail Rates in the United States July 1, 1851 - March 31, 1855

| Distance | Rate | Per |

|---|---|---|

| up to 3000 miles prepaid |

3 cents |

1/2 ounce |

| over 3000 miles prepaid |

6 cents |

|

| up to 3000 miles unpaid |

5 cents |

1/2 ounce |

| over 3000 miles unpaid | 10 cents | 1/2 ounce |

So, our folded letter was mailed only a few months after these new postage rates were put into a effect.

Let me set the scene for what follows. In the 1840s and 1850s, a movement was gaining momentum to encourage mail carriers to provide affordable postage rates. As recently as 1845 (just 6+ years prior), a similar letter from New Orleans to Providence, Rhode Island, would have cost 25 cents in postage instead of 3 cents!

In

other words, many who sent letters treated the surface area on a folded

letter as extremely valuable real estate - and every opportunity to use

it well was taken.

|

| Remember, you can click on images to see a larger version |

Just two weeks ago, I talked a bit about folded letters. This letter consists of a single larger sheet of paper that has been folded in half to create, essentially, four pages - or sides. One side needed to be used as the outside wrapper for an address and postage. The rest would face inward once the letter was fully folded for mailing so the contents would not be revealed unless the letter was opened.

Now look carefully. The parts of this page (or side) that would get folded in is covered with printed information. The sender of this letter was not about to let that valuable space go unused.

Two more sides on this folded letter are also covered with pre-printed material. The content itself was referred to as a price(s) current, or a market report, that provided recent product volumes and values in the New Orleans area. Much of the report centers around agricultural products, which makes sense as the letter was mailed by a Wood & Lowe, who were cotton brokers in New Orleans.

The printed content

actually provides information for multiple years leading up to September

of 1851. The text itself is actually pretty small. If a person did

not need reading glasses before they started reading this folded letter,

they might once they completed the task.

One of the four pages also includes a personal note to the recipient. The docket at the top reads "Sept 8th, 1851," the day prior to the New Orleans post office placing the red postmark on this cover. The letter starts with discussion of the cotton crop. Otherwise, this is pretty much a standard business letter that is essentially encouraging the recipient to participate in the purchase of the year's cotton crop.

Some of you might remember that printed matter, such as what we saw on three sides of this letter sheet, qualified for a cheaper postage rate. If this item had not included this personal correspondence, it would have also qualified. But since this sheet was printed in such a way that one side was left blank, the intent was clearly to allow space for the personal sales pitch.

The handwriting here is like much

handwriting, there can be places where it is harder to read. But, what I

am going to show you next will make this look simple!

Our second folded letter was mailed in New York City to Southampton in the UK. It entered the mailbag to cross the Atlantic Ocean on July 8 and was taken out of the mailbag in Liverpool on July 18. The letter was carried on the Inman Line steamship named City of Boston, which arrived at Liverpool on July 18 (which nicely matches the postmark for Liverpool at the left).

There are two postmarks on the back of this letter. One is a London postmark for July 19 and the other is a Southampton postmark for the same day. So, we can guess that Edward Palk received this missive at that time. The docket at the left in dark ink reads "Mr Parsons June 1865." Indeed, the letter inside is datelined "Cleveland, June 1865," which provides us with the date and location for the starting point of this letter. After taking some time deciphering the contents of the letter, it seems it was written over a period of several days, and it is possible Mr. John Parsons was traveling as well.

Everything I say about the contents of the letter is still open to further study - because reading the letter is not easy.

Rather than spend more time telling you why it was hard to read, let me just show you.

This is the first page of the letter. Or at least, this is where the letter starts. Mr. Parsons used a technique called "cross-writing" in an effort to avoid using more sheets of paper that would have caused the letter to exceed a half ounce in weight. Exceeding that half ounce would have required another 24 cents in postage and, apparently that cost was worth expending the effort of writing in a lighter ink first in one direction. Later content was written OVER the lighter ink in a darker ink and going in a direction that is vertical, instead of horizontal, on the sheet.

This is certainly a technique that was developed during a time when the cost of mail was extremely high. But, by the time we get to 1865, postage had come down significantly. This interesting blog by Kathy Haas makes a valid suggestion that cross-writing might not have always been used because the writer was unable to afford the cost of paper and postage. It is possible that this was "an ingrained habit or a practice associated with virtuous thrift."

In other words, it

is possible that Mr. Parsons was signaling his own virtue to Mr. Palk

by... um... making it really hard for Mr. Palk to read the contents of

the letter.

|

| the top of the page shown above |

The letter opens, "My Dear Friend..." But, after taking a few moments to attempt to read this writing, I have come to the conclusion that Mr. Palk was either truly a very dear friend OR this was a passive aggressive way to let Mr. Palk know who was better than whom.

The

letter actually starts out with some business, acknowledging a draft

(for money transfer) and discussion of the status of an account. The

rest of the letter seems to cover a lot of ground. On the whole, the

letter seems to be quite conversational - so perhaps Mr. Parsons did

consider Mr. Palk a "dear friend."

Later in the letter, Mr. Parsons speculates on some issues he has read in the paper about Europe. For example, I see mentions of the Fenians, an Irish nationalist society on this page where the writing runs vertically. But, I find it very interesting to read his comment that "now that the war is over..." houses were becoming available that were less expensive to purchase than rent. Apparently, it had been difficult to find rental properties "at any price."

Some of the

cross-writing has a notation that reads "July 3," which makes it clear

that this letter was written over a period of days. Mr. Parsons follows

the date by saying "tomorrow will be a great one for firecrackers and..

speeches." No doubt, in reference to Independence Day celebrations.

Perhaps someday I will make the effort to read this letter in its entirety. Or, I'll just take something for the headache I feel coming on about now. The handwriting itself is fairly legible. It is more a matter of familiarity. Words like "their," "friend," and even "acknowledge" are recognizable because they are common words I know and use. But, because we are not familiar with the names, time-period references, colloquialisms and subject areas that the writer and recipient are, we are often left to guess - often badly - at the key words that could unlock the content fully.

Bonus Material - Shubael Hutchins

Going back to our first letter, we find that it is addressed to S. Hutchins & Co of Providence, Rhode Island. We could be dealing with either Shubael Hutchins (2nd of that name) or Shubael Hutchins III, both of whom might well have been part of the business at the time. The latter Shubael apparently served as president of the American Bank in Providence from 1855 to 1868. It is a decent guess that the former was a businessman who dealt in dry goods at either the wholesale or retail level.

With

that information, I made the educated guess that the elder Shubael

Hutchins was the namesake for a drygoods business - hence the reason he

would receive a letter from New Orleans regarding the cotton crop. The

Colenda Digital Repository provides support for this guess as it features a letter sent to Hutchins regarding damaged cotton bales.

|

| A small portion of the price-current |

One never knows what you can uncover once you are fairly sure you have identified the recipient (or sender) of a piece of mail. In this case, I actually ran into a court case regarding the will of Shubael Hutchins (the 2nd), and the opinion was published in 1907. Since Hutchins had died in 1867, this certainly gives one pause - a forty year gap to finalize parts of will seems excessive to me.

Apparently a key issue being considered was this part of the will (most of the rest of the will had been executed successfully):

"To the treasurer of any one or more societies or organizations whose object is the improvement and education of the colored people of the south, I give the sum of ten thousand dollars for the uses and purposes of said societies but I leave it wholly to the judgment of my said trustees as to the time when, how much of, and to what society or societies or organizations said sum or any part thereof shall be paid having reference to the ability of my estate and the Efficiency of any of said societies in the above object"

At issue was the contention by the trustees that they could not find an appropriate society to give the money to, so they wanted to be granted the ability to NOT follow through with this portion of the will. Cutting right to the chase, the court held that the money was for a valid charitable cause and was not void due to "indefiniteness or uncertainty."

In other words the ruling was saying "figure it out people and get that money where it is supposed to go."

Perhaps

there were stipulations that the organization needed to be in Rhode

Island. But, it certainly wasn't a matter of finding where the people

of color might have been. Shown below is part of a map produced in the

early 1860s and based on 1860 census data. I selected the areas closer

to New Orleans to make the point. Each county was shaded to illustrate

the percentage of the population that was enslaved. The darkest shade

indicates populations where slaves comprised 80% (or higher) of the

total. Much of the area upstream form New Orleans on the Mississippi

River fit that description.

|

| Portion of map published by US Coast Guard, from American Yawp. |

I find the irony of this donation from the estate to be very interesting. Clearly, Hutchins and his business benefited greatly from cotton. Cotton, in turn, relied heavily on slave populations to produce sufficient crop for people like Hutchins to trade. Did Shubael Hutchins make the connection and add this into the will as salve for his soul? Were the trustees of the estate reluctant to follow through with his wishes because they didn't really want the colored people of the south to become educated?

To put this in perspective, $10,000 in

1867, the year Hutchins died, had the same buying power then that

$380,000 has in today's world. It wasn't going to keep a school or

other organization running indefinitely, but it certainly could have

made a difference for a few people.

For those who might like to learn more about the role of cotton in the US Civil War, I found this blog to be interesting. If you want something with even more depth to content with appropriate citations, this article on American Yawp fits the bill.

While we will never know the full story of Shubael Hutchins and his bequest, these are events and issues worth pondering and considering - thank you for allowing me to do so in today's writing.

I think we'll call it a day. I hope you enjoyed this edition of Postal History Sunday.

For

those who are curious, I also uncovered interesting material on Edward

Palk (our second featured item), which I think I will reserve for future

Postal History Sunday! Hey! I need to save something for later, don't

I?

Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

--------------------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your input! We appreciate hearing what you have to say.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.