Welcome to this week's edition of Postal History Sunday!

It's been several weeks since I did a full introduction. So, if you're new here or if you need a refresh, Postal History Sunday is written weekly - and hopefully not weakly - by Rob Faux (yep, that's me). The first Postal History Sunday was offered in August of 2020, as part of my own effort to reach out to others who might be feeling the negative effects of the pandemic. My intent then is the same as it is now. I hope that I can share something I enjoy with you in such a way that you might be entertained whether you know a lot about postal history or you just happen to be passing through. Perhaps you will be able to set your troubles aside for a few moments and maybe, just maybe, you'll learn something new!

And now, without further todo, let's look at a

piece of postal history from the year 1868. This item was mailed from

Richmond, Maine, in the United States to Callao, Peru.

Richmond is located south of Augusta, Maine, on the Kennebec River. For those of you who are vegetable growers, you might recognize the name "Kennebec" for the popular potato. That potato variety was developed in Maine at the Presque Island USDA facilities and introduced in 1941. This document from that time period discusses those facilities and their program (page 415).

I bring potatoes up because they, and other food plants, are grown on land where additional fertility is often needed to maintain crop production year after year in the same location. The cover above actually has a connection and it will be interesting to see how I get to making that connection!

This envelope has two postage stamps, one represents 24 cents of postage and the other 10 cents. The 34-cent rate per 1/2 ounce from the United States to Peru was in place from October of 1867 until February of 1870 and unlike many postage rates of the time, was actually an increase from the prior postage rate (22 cents).

Letters to Peru from the US typically traveled by steamship to Panama, crossing the isthmus by land if the letter originated from a location east of the Rocky Mountains. Once on the west coast of Panama, a steamship under British contract would carry mail destined for the west coast of South America.

At this time,

ten cents of the total postage was kept by the United States to cover

their costs, but they had to pass on 24 cents to the British - hence the

red "24" at the bottom right.

The letter itself was intended for Zacheus Allen, who was apparently on board the ship America under the command of Captain Morse. The directional docket instructs the postal service to put the letter into the hands of the US Consul in Callao so they could arrange to get the letter to Allen.

This docket reads " Ship America, Capt Morse, care American Consul (ship loading at Chinci Islands)"

Zacheus Allen was on one of a large number of ships likely awaiting a load of guano from the Chincha Islands, a process that could be quite lengthy. So, it is likely that the various consuls for different countries had a process for taking mail to bored sailors waiting for their ship's hull to be filled...

with poo.

Yes, you heard me correctly, these

ships were waiting to be filled with old bird droppings that were going

to be sold as fertility amendments elsewhere in the world (primarily

North America and Europe). And now you see the link between Kennebec

potatoes and the topic at hand. This is all about soil fertility.

Guano became big business

|

| The Great Heap from Alexander Gardner's Rays of Sunlight from South America |

Guano had long been used, in a careful and guarded fashion, for fertility supplements by the Incan empire for generations. The Incans were fully aware that this resources was renewable as long as the seabird population was encouraged AND the lmited existing resources was not over-exploited. Of course, European and North American agricultural systems tended to extract more from the soils, requiring various sources to replace fertility (nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium). As a result, these ag systems had an almost insatiable need for products that could deliver that fertility.

Alexander von Humboldt, during his travels in South America, became aware of the use of guano and took samples back to Europe with him in 1804. Scientific analysis of the day confirmed its value. And thus began a process of extraction and export that would last for decades on the Chincha Islands - where the supply would run out in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

If this topic interests you, you could get a nice summary here at the Atlas Obscura by Cara Giaimo. Or, if you want an in depth work on the topic, Gregory T Cushman's book titled Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World seems like a good place to go.

|

| Ships awaiting guano at Chincha Islands 1865, from Gardner book |

The largest of the Chincha Islands had guano that reached depths of 200 feet, which can be seen by looking at the first photo of the "Great Heap." Workers, some free laborers and others indentured, would use pick-axes, shovels and carts to mine the substance. A fine article by W.M. Mathew titled "A Primitive Export Sector: Guano Production in Mid-nineteenth Century Peru," describes the effort of extraction, movement and loading as dirty, slow, difficult, and inefficient work. Significant amounts of guano was lost into the ocean during the loading process and in dust that filled the air.

"When the loading started, all inside doors and windows [of the ship] were closed and tightly covered with canvas to prevent the toxic dust from filling a ship’s crew spaces. Loading crews were limited to twenty-minute shifts in the cargo holds, and the rest of the crew climbed to the tops of the masts to breathe fresh air." - from this Smithsonian source titled the Guano Trade.

According to the work by W.M. Mathew, there was one report that stated as many as 160 ships were awaiting loading at one point in 1869, and this was at a point when the supply of guano on the Chincha Islands was dwindling. The same source suggested that this meant there were 4000 people on board those ships - all waiting for a load of bird manure.

I think you can now get an idea as to how valuable a letter from home - and an American Consul office that would arrange to deliver that letter - could have been.

|

| Guano mining from the Gardner book. 1865. |

Enough to fight for?

|

| Battle of Callao from wikimedia commons |

The value of seabird excrement was such that the Spanish actually attempted to use the Chincha Islands as a bargaining chip, since guano production produced a significant amount of the Peruvian government's revenue. Spain occupied the islands with 400 marines on April 14, 1864 and proceeded with a blockade of major ports in Peru (including Callao).

Peruvian

and Chilean forces (and later some help from Ecuador and Bolivia)

eventually forced Spain's withdrawal (by 1866). This would not be the

end of hostilities that had to do with the extraction of materials for

fertilizer. The War of the Pacific (1879) between Chile, Bolivia and

Peru was at least partly due to a desire to control both guano and

saltpeter deposits.

Saltpeter - staying in the fertilizer game

Let's go back to an envelope I featured in an earlier Postal History Sunday for a couple of interesting tidbits that you might enjoy!

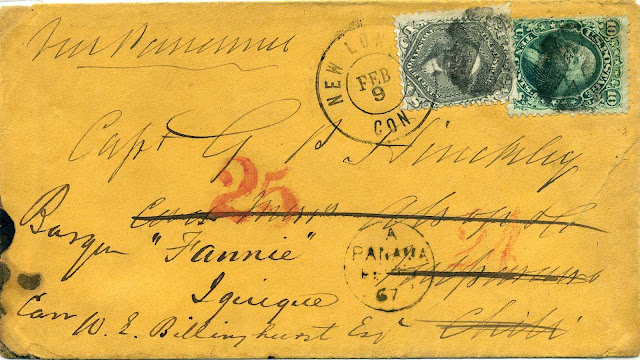

This envelope was sent from New London, Connecticut to Valparaiso, Chile, in 1867. The recipient was a Captain Hinckley and his ship must have been the barque "Fannie." His mail was sent to Messrs Alsop & Co, which was a common location for United States ship captains or US citizens to have their mail sent if they were visiting Chile.

Foreign mail to Chile could only be pre-paid to the point

of entry into the country. Chile charged an incoming foreign mail fee

equivalent to 5 centavos (July 1853 to December 29, 1874). In

addition to the incoming mail fee, incoming mail required two times the

domestic internal rate (10 centavos) for a total charge of 25 centavos

collected from the recipient at the point of delivery.

This letter was initially sent to Alsop & Co in Valparaiso, but they sent that letter on to W.E. Billinghurst in Iquique, which was in Peru at the time this letter was sent (1867). We can assume this letter caught up to Capt Hinckley there since there doesn't appear to any more travels recorded on this envelope.

Mr. Billinghurst was listed as a shipping agent for Lloyd's

in Iquique during the 1860s and was, like many who worked as a

shipping agent, also the representative for many other concerns. Anyone

involved in trade, especially of Chilean saltpeter or guano, had likely

heard of

him. So, it might not be surprising to hear that his demise in the 1868

earthquake was specifically noted in newspapers throughout the world.

Iquique, despite being located in a desert region, was a port of prominence because that desert had strong deposits of sodium nitrate (Chilean saltpeter) - used for fertilizers. With the guano deposits rapidly being depleted, attention was shifting southward to the Atacama desert - and to Iquique - as the primary port of departure for ships laden with Chilean saltpeter as a fertilizer product. In 1867, nearly 116,000 tons of saltpeter were exported by Peru. This amount declined the following year, likely due, in part, to the 1868 earthquakes.

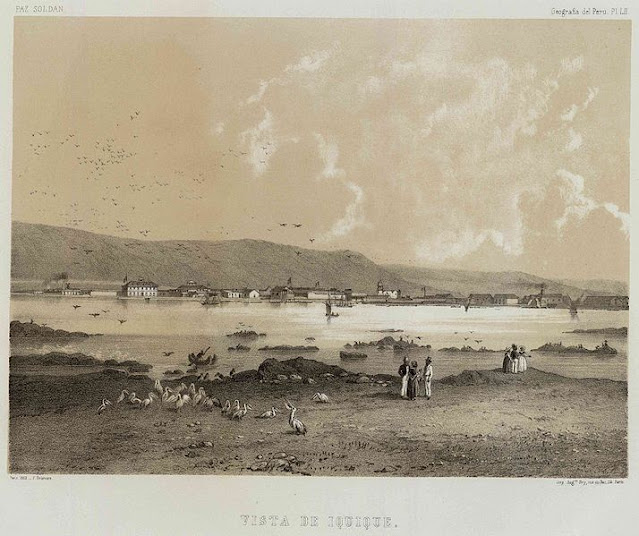

|

| Iquique 1865 by Mariano Felipe Paz Soldan from wikimedia commons |

And then, there was always bone meal

This envelope was first featured in a Postal History Sunday titled Poo d'Etat

The postage stamp is a 2 cent denomination from the 1869 US issue and it pays the rate for items that were classified as a "circular." The rate for this class of mail was effective from 1863 to 1872 and allowed the sender to put up to three copies of the circular into one cover (envelope or wrapper of some sort). To qualify, the contents could only be printed matter (with no written personal messages placed in addition to the printed matter). The envelope also needed to be left unsealed so the postal clerks could inspect the item to be sure it met regulations.

I recognize that some people are a little squeamish with the idea of using ground up animal bones as a soil supplement, but you need to consider the relative resource efficiency of using bone meal versus other sources of phosphorous. Most farms included animals in their operations, some of which were raised for meat. Rather than simply discarding the bones, they could be used by being ground up and placed back into the soil so the cycle of life could continue. The goal of companies like this was to make the bone meal "soluble" so it be more readily available for uptake by plant roots.

This company directly compares their product to the Peruvian guano and, of course, makes a case that their product would be better. In particular, they cite a much more favorable price than the expensive guano being shipped from South America.

And now you know, manure was, and is, big business. And I just got you to read all about it in today's Postal History Sunday! No wonder I enjoy writing these posts.

A short bonus material section

Zacheus Allen, the recipient of our first letter and sailor, at the time, on the ship America, actually turned up with a little searching in a strange place. He ran into a spot of trouble as the First Officer on the Matterhorn during a trip from Cardiff (Wales) to Callao a year or two after his time waiting for a load of Guano in 1868.

This document Criminal Case Files : 1863-1917 includes charges against Allen that were of a serious nature. The case is summarized there as follows:

"Indictment for beating, wounding, assaulting and for cruel and unusual punishment and for the murder of Moses Blake, mariner, using a four foot capstan and a pistol and then beat him up"

There was apparently a case for self-defense that even led to a letter to then President U.S. Grant.

|

| from the Papers of U.S. Grant, Vol 20, Nov 1, 1869 - Oct 31, 1870 |

You

might notice that the US Consul for Peru was involved in this situation

as well. Williamson had taken the post earlier in 1870, so was not the

same person who was in charge of the consulate at the time Allen

received the letter we show at the beginning.

The case results are also from the Criminal Case File document:

Detailed description of the assault and the testimony; Consolidated with cases 504 & 505; 31 Nov 1870 Verdict not guilty for case 503; nolle prosequi for case 504; guilty of beating Moses Blake for case 505, fined $10 and discharged; Case 506 murder - separate, 3 Nov 1870 ordered nolle prosequi

For those who do not know (and that included me until a few minutes ago) nolle prosequi is

-----------------------------------------------

Thank you for joining me for Postal History Sunday. I hope you enjoyed reading this and that, perhaps, you learned something interesting and new to you.

Have a great remainder of the day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your input! We appreciate hearing what you have to say.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.