Welcome to this week's Postal History Sunday entry on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. Everyone is welcome here in this corner of the internet where I explore a hobby I enjoy and share it with those who have anywhere from a passing interest to those with a passion for the subject.

It's time to put on the fuzzy slippers and grab a favorite beverage or snack. Always be careful of your food and drink around the paper collectibles (and your keyboard). Let's see where this week's entry takes us!

-------------------

One of my attractions to postal history is that it provides opportunities to learn and to expand my own knowledge and understanding within postal history and of the world around me. A couple of weeks ago, I explored how I can dig deeper into something I actually know very well. In that blog, titled With This Ring, I illustrated how my understanding for the use of a particular postal marking has become more complete over time. I might have had sufficient understanding before, but now I can say I know that topic much more completely and with much more depth.

I also find myself pushing at the edges of the breadth of my knowledge. After all, I will be the first to admit that there are many subject areas within the hobby where my only expertise is my ability to use basic tools for research and learning. But, I am always probing and expanding on what I know - and I thought I would share some of those edges in today's Postal History Sunday.

Postal services beyond letter mail

I will readily admit that most of my collection, and therefore, a significant portion of my expertise, lies with the mailing of items that qualified as letter mail. In itself, that area has plenty to explore and plenty to enjoy. However, people have long mailed packages and newspapers, which have some characteristics that are unique to them. And, there are additional services that could be applied to letter mail and packages, such as registration and insurance.

At first glance, the envelope shown above looks like so many other pieces of letter mail. It has two postage stamps that have been cancelled with a grid of dots, shaped like a diamond - each with the numeral "2177" in the middle. There is a postmark at the top left that shows us it was mailed from Malaucène, France on October 15, 1867 and the address panel tells us that the destination is Nîmes (also in France).

I had two clues that told me this was not a typical piece of letter mail when I first saw it. One should be fairly easy for everyone to spot.

It's in bright red ink and it does stand out. Even if you did not know that it was something different, it calls attention to itself. The other thing that I noticed (and you might not have) was that the amount of postage was not an amount that a regular internal letter in France would require in 1867.

Part of the knowledge I do own with respect to French internal mail is this rate structure. A piece of letter mail might have 20 centimes, 40 centimes, 80 centimes, 160 centimes (and increments of 80 centimes from there). This letter has 60 centimes of postage, which tells me something different is going on and I need to explore further.

But, wait! There's more!

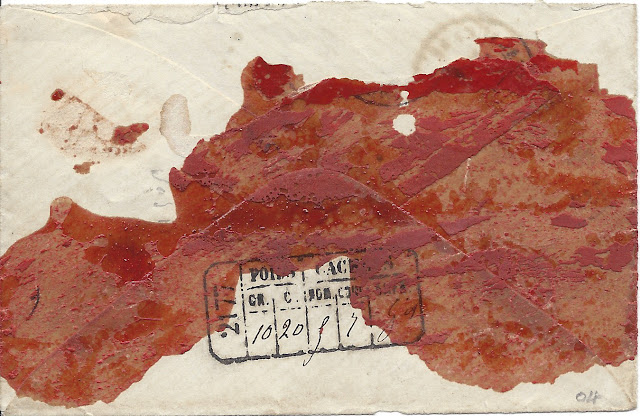

The back of this envelope also shows some characteristics that are not common for letter mail of the time. Apparently, red wax was liberally applied to the envelope flap's seal to the rest of the envelope. And, there is a box marking that I usually don't see.

I did, at the point I first saw this item, have some familiarity with what is called a lettre charge’. For the U.S. equivalent, we can look to registered mail. Something like this from 1918:

The three cent stamp paid the regular letter mail postage and the ten cent stamp paid for the registration service. There is a purple box that indicates that the item is registered and it includes a registry number to aid in the tracking of this item as it traveled through the mail. Essentially registry was a way to attempt to provide additional security when someone mailed items of value by paying the postal service to track it more carefully than a normal letter.

This was also true for lettres charge’ in France, just like the 1865 item shown below:

This wrapper carried an official court summons to a local address. We see the red Charge' marking once again and there are thirty centimes in postage. Ten centimes to pay the discounted rate for the local letter mail and twenty cents to pay for the "registry fee." But, this item does not have the box on the back like our new item does.

Let me remind you what the first envelope in question looks like...

It turns out there is a step beyond registry - and that would be postal insurance to protect against loss. And there were two options at the time (1867) in France:

- valeurs cotée (insurance for a value assigned after inspection by the postal clerk)

- valeur déclarée (insurance value declared by the sender, but not confirmed by the postal clerk)

Our new item is an example of valeur déclarée - and it turns out figuring the cost of such an item requires a slightly different understanding than regular letter mail.

The cost is split into three parts:

- A special postal rate that is calculated based on weight

- A flat additional fee of 20 centimes (the registry fee)

- Payment for insurance to cover the declared value of the item being sent.

Only the first two could be paid with postage stamps. The third cost was paid in cash to the postal clerk.

The "charge box" on the back gives us some of the information we need to calculate the postage required. Note first that the number "2177" is at the left. This is the number assigned to the Malaucène post office and it matches the number in the cancellation on the stamps (cool, eh?). The weight is written in the first two columns in grams (gr) and centigrams (c.). So, the weight of this item is 10.2 grams.

This table shows us the special postage rates for this type of item - and since this weighed more than 10 grams, it would have cost 40 centimes in postage PLUS the flat registry fee of 20 centimes.

Total postage cost = 60 centimes, which matches the stamps shown on the front of the envelope! So, far so good!

But how much insurance did this person take out on the contents?

Well, that is actually written on the front side of the cover and on the left of the envelope. It reads "quattres cents francs," which translates to "four hundred francs."

The rate for insurance was 10 centimes for every 100 francs in declared value. So, the sender would have had to pay 40 centimes for the insurance in addition to the 60 centimes in postage stamps.

And this is part of where I was lost for some time. You see, I am used to seeing the word "franco" on letter mail during the period - and that essentially means "paid." And, I am also used to postage and costs being rated in terms of centimes or decimes in France. For a long time, I thought this read "4 centimes paid," which made no sense and it took me down all sorts of wrong paths!

You see, according to references the minimum cost for valeur déclarée was 10 centimes - and amounts could only change in 10 centime increments. Which made me wonder if it was valeurs cotée - where the cost was a percentage of the determined value. This is where past knowledge can blind you, at least momentarily, to the truth of the matter. It did not even occur to me that this was equivalent to someone in the US writing "four hundred dollars," and I was not even thinking that they would write the declared value on the envelope instead of the cost of the insurance.

And that, my friends, is how you push the edges of your understanding out just a little bit further.

I can get this from Denmark to France, but...

And here is an example of a postal history item that is pushing the borders of my knowledge today. This letter is from Christiania, Norway (now known as Oslo) to Bordeaux, France. The letter was mailed in July of 1852 and was taken via Denmark, Hamburg, the Thurn & Taxis mail system, and then entered France at the border with Belgium.

I can tell you that the big, black "11" marking on the front indicates that 11 decimes were due to pay for the postage to get the letter from Denmark to Bordeaux. I can tell you this rate was effective from August 1, 1849 until February 28, 1854 and the rate was 11 decimes for every 7.5 grams in weight, payable when the recipient received the letter.

I can also tell you that this letter was prepaid from Christiania to the border of Denmark!

The docket at the lower left on the front reads "fco dansk grandse," which essentially translates to "paid to the Danish border." So, the sender paid SOME of the postage to get it part way to its destination. The recipient paid to get this item FROM the border to Hamburg and then to France.

But, I can't tell you with the knowledge I have HOW we get from Christiania to Hamburg. I can't tell you how much the sender paid to get the letter that far. I do not know what the rate structure was for mail from Norway at the time and I don't know what time periods these rates were effective. I think the weight unit used was the "lod" in Norway, but that's about it.

And, I have no idea what the marking shown below might be for - or if it is important to reading the story as to how this letter traveled from here to there.

There are all sorts of barriers that could encourage me to just accept what I know now as a "good enough" explanation. It is likely the best resources for my answers are written in Norwegian or Danish, and I know neither. Most places that I go to look for information show very little for the Nordic and Danish postal systems, so I have far less familiarity with the area as a whole.

But, this has not stopped me before. There was a time that I wasn't even sure how to figure out a basic letter in France - and now I can tell something does not fit the standard letter rates by just looking at it.

This is another example of how I keep pushing the edges of what I know - and it leads to even more edges to explore.

One more edge

It turns out that I am often pushing at more than one of the edges of my hobby at any given time. Sometimes, if progress just doesn't seem to be happening, I will set an item aside until I get the desire to push again. Shown above is just such an item.

This is an envelope mailed at Oudewater, Holland to Arnhem (also Holland). There are no postage stamps, just a big blue label at the bottom left.

My basic understanding is that this is a letter that came along with a package. In this case, there is actually reference to TWO packages. If you look at the top, you can see the words "met 2 pakken" - "with two packages." And, if you look closely, you will see the word "franco" on the third line, that tells me the postage was pre-paid - I presume for the packages and the envelope. It was mailed at the railway station (Spoor) and taken by train from one location (Oudewater) to the next (Arnhem).

But, that is where my knowledge ends. I have never really looked at this type of item before, though I seem to recall glancing over an article about these Dutch labels once in my lifetime.

This is how it begins - maybe we'll see some progression one day if I write about it again in a Postal History Sunday.

Bonus Material

I realize I might have left you hanging with a couple of questions earlier and I thought I would give you a little more here - at the end of the blog.

Why all of that red wax?

Postal services used various ways to illustrate that the seal for a registered (or insured) letter had not been broken. One way was to place postal markings at each seal location - like this:

Notice the purple markings state the item is "registered" and they are placed where the back flap of the envelope seals the envelope closed. If this marking did not line up, that would be an indication that the letter had been opened. The red wax served a similar purpose. It was an attempt to illustrate that no one had opened the envelope prior to delivery.

What other information is held in the charge box?

I have already mentioned the post office number at the left and the weight of the item in grams and centigrams in the first two columns. The remaining columns under the word "Cachets" are something I am not quite sure I fully understand myself. Laurent Veglio, who has expertise in French postal history, tells me that "cachets" refers to "seals," and the columns stand for quantity (nom), color, and design.

The next step is to understand the scrawls in those boxes and how they relate to this particular envelope. Once I push that edge a little further out, I'll let you all know in a future Postal History Sunday!

-------------------------

Thank you for taking the time and allowing me to share with you something I enjoy. I hope you picked up some new tidbit of knowledge and/or that you found your time visiting me here to be pleasantly spent.

Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your input! We appreciate hearing what you have to say.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.