The following is a cross-posting of my work published on the Pesticide Action Network blog. I try to share what I write for PAN here every once in a while so you can all see what I am up to! Thank you for considering my thoughts and words.

-------------------------------------

There are many voices who argue effectively and well that agroecology holds the answers that can address the shortcomings of our farm and food systems. I have added my voice to theirs as a farmer and steward of my own small-scale, diversified farm in Iowa. Many make the mistake of thinking that this battle has just begun, even when there is plenty of evidence that many of the techniques of growing that would be better for our world have been discussed and promoted for generations.

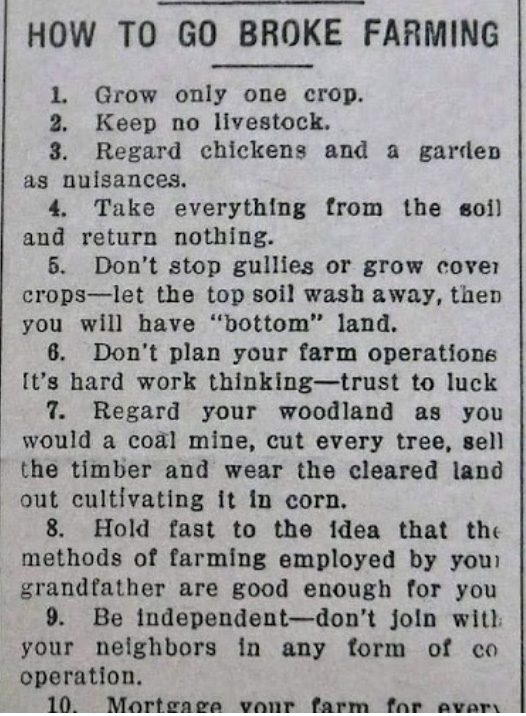

How to go broke farming

As a small-scale farmer, I have a membership in a hard-working community of like-minded land stewards who often share knowledge and information freely with each other. Several months ago, an old newspaper clipping from the June 17, 1927 Farm and Dairy publication was passed from person to person through email and social media platforms.

This is not the only historic example of farming wisdom that has been circulated in recent years. I have viewed documents from the 1940s, 1870s and, yes, even the 1700s that discuss farming practices that, for some reason, have been historically overlooked by many of those who farm.

Here is a summary of this article:

- Grow only one crop

- No animals on the farm

- Take everything from the soil and return nothing

- Let top soil wash away

- Don’t plan

- Cut every tree and grow corn

- There is no reason to learn and adjust your farming methods

- Don’t cooperate with other farmers

This list, assembled by the University of Tennessee Extension, outlines some of the approaches that were well-established as bad practices for a successful farm in the 1920s. In my opinion, this is all just common sense. Of course you should grow a diverse set of crops, using a carefully planned crop rotation and implementing intercropping. The concept of integrating animals for both fertility and diversification on the landscape isn’t hard to understand. Protecting the health of the soil feels like it should be a basic tenant for all food producers. And, the concept of continued learning and the spirit of cooperation between growers just seem like necessary tools for a successful farming system.

Apparently the lesson is difficult to learn

As I read this news clipping from 1927, I asked myself why they felt it necessary to point out that these practices were a bad idea. That’s when I realized that the authors were fighting the same battle we find ourselves fighting today. There were a significant number of farmers and landowners in the 1920s, just as there are today, that fail to recognize that farming needs to be a complex operation.

Yes, you heard that right. The way many of our grandparents and previous generations farmed was less than optimal. And it feels like there are plenty of folks out there who are quite happy to maintain that tradition in the present day. The only real constant for generations in the United States has been a willingness of too many people to ignore the principles of land stewardship.

Perhaps the only difference is that people have found a way to continue making money despite abusing the land they farm. If anything, the changes in our food and agriculture systems since 1927 have made it difficult to farm well. Instead, our systems reward the pesticide and synthetic fertilizer industries (among other big ag businesses) and place hurdles in front of anyone who might like to engage in being a steward-farmer. Bigger farms growing single crops in larger fields that sit bare during the winter months while the soil erodes is what we currently reward. We prop these farms up with our governmental programs so they can feed the ag industry — even if we know that this model would fail as soon as we kicked these false supports away.

Eventually some of these false supports for poor farming — such as herbicides — are no longer able to hold the wolf at the door. The weeds are adapting and the strain of continuous tillage and pesticide use is making our soils less fertile and less productive. The deep, rich soil we have in states like Iowa isn’t as deep and rich as it once was and we will be called to pay for our debt to the land.

If we spent more time caring for the land, it would take care of us. We wouldn’t need to rely on the next new and novel technological solution for pest control, soil fertility, and weed control. Instead, we could use those tools in only the most exceptional of circumstances, relying on complex and healthy systems instead.

We can still learn and act to change

I recognize that there are many people, from every generation and many different backgrounds, who have farmed and been true stewards of the land. These people, some Indigenous, some people of color, some white immigrants, have stood out from the crowd. They are often seen as the exceptions (and sometimes hailed as exceptional) and they often feel the pressures of not going along with the corporate plan for agriculture during their time.

This is, in my opinion, backwards from the way the world should be. These are the food growers and land stewards who should be faceless (except when they are in their own communities) because there should be so many of them. Those who should stand out as exceptions are those who fail to farm well. And then, our strong farming communities could provide the support they would need to join the rest in being positive and effective stewards of the land.

I know, it’s a radical idea. And apparently it’s been radical for generations. Perhaps it’s time for this to be the mainstream attitude?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your input! We appreciate hearing what you have to say.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.