Welcome to the 90th entry of Postal History Sunday, featured weekly on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with this one (the most recent always shows up at the top).

Last week I solicited input and/or interaction with those who read PHS - and I did get some. I would like to thank those who shared kind words with me either in the comments, in social media or via email. I will also continue to solicit input as we approach the 100th Postal History Sunday. See the end of the blog for more.

The weather in Iowa has finally warmed and we actually had a beautiful day where we were able to do some serious work on the farm. This resulted in me looking at the computer screen at 9 pm on a Saturday wondering what I was going to do for Postal History Sunday. The answer? Well, I realized that I had a question that was asked by a couple of individuals (in a couple of different ways) that I have kind of answered in the past - but maybe would be worth revisiting.

What grab's my attention and gets me to consider adding a new item to my collection?

I thought I would answer the question this time around by sharing a few examples of some things that I added over the last couple of years and my reasons for doing so - and maybe we'll all learn something new while I'm at it!

Something familiar shown in a different way

The envelope above was mailed in Paris in July of 1867 and traveled to London, England in the hopes that it would find George Blackwell, Esquire. The contents were most likely a death announcement, which is indicated by the black border on the envelope. If we look at the back, we can see this border is also visible there as well.

This sort of cover is typically referred to as a mourning cover by postal history collectors. The extra little bit of color, even if it is just black, often sets covers of this sort apart. Our eyes get drawn to differences like this, especially if you have been looking at hundreds of envelopes from the 1860s - and you find that any sort of ornamentation or decoration is in the minority. So you take note when you see it.

But, that's not what interested me in this item. Yes, I liked the fact that it is pretty clean. It clearly shows the 40 centime rate for mail from France to the United Kingdom that was in effect at the time. And, I did appreciate that it was a mourning cover. I might have passed on adding it, despite all of that, except for the address.

George Blackwell, Esq, Post Office, St Martin's le Grand, London.

Delivery of the mail to a street address or given location had been commonplace in much of Europe for some time at the point this letter was mailed. Yet here we have something that was simply sent to the post office where it was assumed Mr. Blackwell would come to check for mail.

Again, sending something care of the post office, in the hopes that the recipient would come looking for mail was not terribly uncommon in 1867. But it is still outside the norm - so I pay attention to such things. I paid special attention to this one because most of the items mailed to the post office for pickup that I have look more like this one.

This is an envelope mailed from the United States in 1863 to Paris. It is a double rate letter because the weight of the letter was more than 1/4 ounce and no more than 1/2 ounce. So, thirty cents in postage was applied to correctly pay that rate (15 cents per 1/4 ounce). Once again, the address gives is a street address in Paris, which happened to be the location of a post office in the city.

And we have the words "Poste Restante" on the envelope, which roughly translates to "remaining post." Once again, this letter was sent to the post office so the recipient could go there and pick it up. We can't be sure why this option was used. Perhaps the writer did not have a better address for the recipient. Maybe Charles A Loomis was not terribly wealthy and could not use a bank or some other agent's address for mail. In any event, it remained at the post office until it was picked up or instructions to forward the letter were given.

The thing that caught my attention is that most of Europe, even if they were not French speaking, used the words "Poste Restante" for this service. But, not the United Kingdom. It'll be "Post Office" for us, thank you very much! That, believe it or not, provided the extra incentive for me to add this item to the collection.

Something to puzzle out

Sometimes I pick up an item that isn't too expensive, but I am not entirely sure what it is I've got in front of me. I have SOME idea, but then there is something about it that isn't quite what I expect based on prior experience and my curiosity encourages me to dig into it further.

So, let's start with something similar where I KNEW what was going on.

Both of the folded letters shown here are from locations in Sardinia, which was in the process of merging other parts of Italy into the Kingdom of Italy at the time both of these letters were written. The first was sent from Milan to Mantua in 1860 and the second from Brescia to Mantua in 1861.

Both of them have a "5" on the front that indicated that the recipient should pay for postage due. But, they both also have Sardinian postage stamps, which tells us something must have been paid for.

I understand the second letter. The internal postage rate in Sardinia was 20 centimes for a letter weighing no more than 7.5 grams. Mantova, unfortunately, was NOT part of Sardinia, so the postage was paid only to the border. That meant that the postage from the border to Mantova also had to be paid. At the time, Mantova was under the jurisdiction of the Kingdom of Venetia, which was under the control of Austria.

The question was - why does the first letter have TWO stamps? The second letter has one stamp denominated 20 centesimi. The first letter has two such stamps, for 40 centesimi. I wasn't sure of the answer at the time I acquired the folded letter, but I was pretty sure it had something to do with different weight units being used in Sardinia and Austrian controlled territories.

Sure enough. Sardinia's internal rates was 20 centesimi for a letter up to 7.5 grams and 40 centesimi for a letter up to 20 grams. The Austrian rates were broken up by the loth (about 15 grams). So, the first letter was a double rate letter in Sardinia and a single rate letter in Venetia (Austria).

Or, to make it clearer (I hope), let's pretend this letter weighed 12 grams at the time it was mailed. The post office in Milan was going to see that the letter was more than 7.5 grams, so they were going to require 40 centesimi in postage, which were paid for in stamps. Once the letter arrived in Mantua, the clerk there weighed this and noted that it was less than one loth and knew it would only be ONE letter rate in the Kingdom of Venetia - just like the 2nd letter, which was lighter, but they both qualified for the single rate under the Austrian system.

And those are the subtle little things that, oddly enough, make me happy.

Something that confirms that I am learning

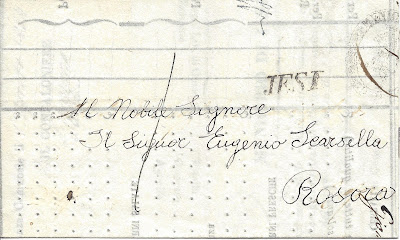

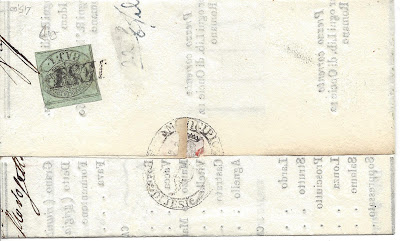

I saw the front of this folded letter and I immediately thought this could be a really cool thing. But, when you collect old pieces of postal history, you often prepare yourself for disappointment. After all, these things are well over 150 years old. A lot can happen during that period of time to pieces of paper. And it is entirely possible that I don't know as much as I thought I did, which means I might not see what I was expecting because I had not yet learned enough to expect the RIGHT thing!

In any event, I saw the squiggle in the middle of this cover and I thought to myself, "I hope I'll find what I think I'll find on the back." I knew, because I now have a reasonable amount of experience in reading squiggles like this one, that this was the number "4." Yes. A four. And, I would not blame you if you looked at me and told me that I was squinting a bit too hard to see it.

I've now seen enough of the postal clerk shorthand for places like the Papal States (Italy) that I have a pretty good feel for this sort of thing. Though I have to admit that there are many times I stare at these squiggly markings for a LONG time before I either give up or ask for some help.

Those postal clerks marked a lot of letters and not all of them were particularly careful with how they marked them. I am afraid they just didn't care that some silly postal historian / farmer was going to want to read those markings and puzzle out how they got from here to there.

How dare they fail to consider my needs?!?

And now that we are done with my righteous indignation. Here is the an example of this sort of letter that I found a few years ago for the Papal States.

I learned with this item that letters that were prepaid have the postage stamp on the front with the address. Those that are NOT prepaid include the amount due on the front, but have the postage stamps on the BACK of the letter or envelope.

The front of this folded circular has a nice clear "1." It's pretty hard for a clerk, even if they are intent on making hard to read squiggles, to mess up the number one. This means one bajocco was due from the recipient for postage.

And sure enough, the back has a one baj postage stamp.

Over time, I have seen many examples like this one. One baj due and a one baj stamp on the back. It makes sense, however, that there are likely to be examples of other postage amounts due with the appropriate amounts of postage on the back. I just hadn't really seen them in any of the places I had time to look. Until I saw the squiggly "4."

So, I was looking for four bajocchi in postage on the back of the folded letter. Did I find it there?

Yes! Two stamps, each denominated for two bajocchi each.

Sometimes, you're just so happy that you have demonstrated for yourself that you are learning and understanding things better than you had in times past that you just have to add an item to the collection.

Three new items - something in common

The common theme with all three of these new items is that they are variations of something for which I have some knowledge. They didn't quite fit with what was already in my comfort zone, but they also weren't so far away that I was taking a "shot in the dark" regarding what was going on. This is one way I like to learn - by building off of what I have constructed for myself thus far. It is also a relatively safe way to acquire postal history items that have not been altered, either purposely or accidentally.

And there you are, a Postal History Sunday for May 8th! I am sure you were wondering if we'd actually manage it, what with all of that farm stuff I was doing earlier in the day. But, we've managed.

Thank you for joining me and I hope you have a find remainder of your day and a great week to come.

Questions for Rob

Manny Brautigam actually came up with a couple of questions that were related to last week's Postal History Sunday offering. Since I DID offer that I would put the answers in future PHS entries - here we go!

"I wonder how poor Gardy came to the conclusion that he had been poisoned?<more content not included in this blog> How much longer is this letter?"

Celebrating the Journey to 100

There are 3 ways you can participate (feel free to participate in more than one way if you wish):

- Ask Rob a question that he can attempt to answer.

- Send Rob a scan of a favorite postal history item and a couple of sentences about WHY this is a favorite item.

- Request that Rob write on a particular postal history topic.

I will feature these questions, favorite items and/or topics in Postal History Sunday as we approach 100. If you do not want me to share your name with your input, please tell me to omit that information if I choose to use your suggestion, question, or favorite item.

Questions and topic suggestions can come from people with any level of postal history knowledge. Prior questions I have received have included "Where do you find all of these neat things?", "How long would it usually take a ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean?", "How did you figure out the United States kept five cents and sent the remaining 19 cents to Britain?", among others.

Similarly, if you choose to share a

favorite item, it need not be old or super rare or really expensive. It

just needs to be a favorite item that is a piece of postal history.

Your reason for making it a favorite is enough!

And finally,

yes, I do reserve the right to decline to use submissions. After all, I

may not be willing or able to answer certain questions or cover

particular topics - I do have a full time job to do and have a farm to

run. But, let's all enter into this with an attitude of cooperation and

I bet this could turn out pretty well!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your input! We appreciate hearing what you have to say.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.